Saqqara 2023 - second week

The Digging Diaries tell the joint mission of Museo Egizio and Rijksmuseum of Leiden to Saqqara.

The excavation project in Saqqara began in 1975. Until 1998 the Leiden Museum cooperated with the Egypt Exploration Society in London. Leiden University (since 1999) and the Bologna Archaeological Museum (since 2011) were also involved in the project.

In 2015, the Museo Egizio joined the project as a third partner.

After two and a half years of delay due to the Corona pandemic, the Leiden-Turin excavations finally resumed in the autumn of 2022. That season, the team excavated the monumental tomb of Panehsy. He was a dignitary in the reign of Ramesses II (c. 1279–1259 BC). The investigation continues this year in and around the tomb to find out more about Panehsy and the area where his tomb was built. In addition, previously excavated objects will be studied, such as fragments of wooden statuettes and coffins.

Digging Diary 2: In Amongst the Coffin Wood

Written by Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod . Photos by Nicola Dell’Aquila (Photographer, Museo Egizio) where not explicitly mentioned

During the 1999 season at Saqqara, the excavators found two wooden coffins near the tomb of Horemheb. These coffins were not in great shape – the damage caused by a combination of moisture, age, and termites had left many pieces more closely resembling slices of Swiss cheese than the sturdy wooden coffins in which their owners had received their final rites. They were therefore not exactly what you might consider, “museum quality”. After they were studied and published, they were therefore not put on display but laid in a storehouse in Saqqara near their original resting place. There they slept until this year, 2023, when they were awakened once more so that we might learn new information about Egypt’s ancient past.

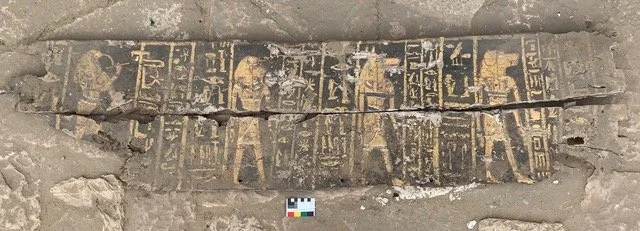

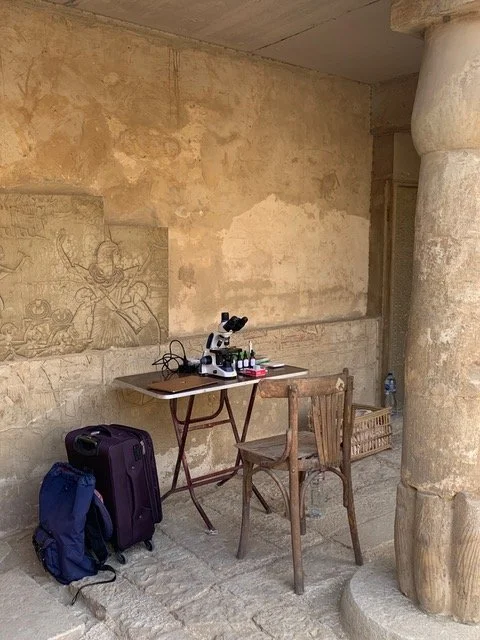

Parts of the rectangular and anthropoid coffins found in 1999 and restudied in 2023.

I am Dr. Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod. I am an archaeologist that specializes in the analysis of ancient wooden objects – and I’m particularly obsessed with Egyptian wooden coffins. One of the goals of the excavation season this year was to complete a more thorough analysis of the pieces of these coffins before turning to a study of the wooden remains from more recent excavation seasons.

As we took the pieces out of the storeroom, the poor preservation discussed in the original publication was immediately obvious – and some additional critters had established their homes in the tunnels and holes left by their insect predecessors. But it is this fragmentary, dare I say, “shabby” state, that allows these pieces to reveal information that their more pristine coffin counterparts conceal beneath perfect layers of plaster and delicate gold leaf. In this state, it is possible to take small wooden samples from multiple areas of the coffin, peer into the coffin joints, and document the tool marks that are usually invisible on a complete object. This helps us to understand what materials were used for coffin construction and provides a glimpse into the movements and choices of carpenters whose stories are otherwise so often lost and overlooked in favour of the history of kings and conquerors.

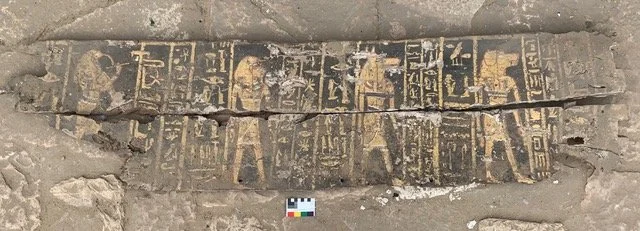

Dr. Caroline Arbuckle MacLeod analyzes wooden objects with her microscope in the tomb of Horemheb.

To identify the species of wood used for each object, I make thin sections of the wood samples and examine the wood anatomy under a microscope. Each tree has a unique profile and looks pretty spectacular up close! When working in the field, I set up a mini laboratory for my analysis. This season I was lucky enough to be working from the tomb of Horemheb, surrounded by some of the most beautiful reliefs I have ever seen. I analyzed many of the coffin pieces as well as the tenons and dowels – pieces of wood that are used to hold the different parts in place. Ultimately, I found that all the larger parts of both coffins were made of sycomore fig, while the dowels and tenons were made of either acacia or tamarisk. This assortment of woods tells us that the carpenters selected from trees that grew locally. They picked sycomore fig because it is easy to work and grows big enough for coffin planks – and has a special religious significance connected to the goddess Nut. They joined the pieces with woods that are harder and better for holding everything in place – they knew their craft, and selected their woods carefully.

A microscopic image of one of the wood samples from the coffin – it is sycomore fig!

Next I looked for evidence of tool marks. Tool marks are incredible because they represent movements, frozen in time. They can connect us to the craftspeople who built these objects more than 3000 years ago! Take a look, for example, at just the foot of this coffin – or rather, take a look at the back – the part that would usually be covered up by additional pieces of wood and paint. Across the back, we can see saw and chisel marks, the first rough cuts used for the initial shaping of this piece. Then the carpenters drew red lines to mark out where they would cut the dovetail joint that would hold the pieces of wood together – but later they made a correction and cut it smaller, leaving a faint red line behind on the wood, parallel to the final cut (an ancient instance of measure twice, cut once!). To cut the joint, they started with saws, and a tiny knick at the top shows that they cut just a tiny bit too far, but no matter, that would be covered up later. They then took chisels to remove the last bit of wood at the back of the joint, since their saws would not fit in this space. These final rough chisel marks are left unfinished, again destined to be covered up by later construction steps. All these choices and movements are visible to us today only because time and termites ultimately undid the carpenters’ hard work. While these coffins may not seem beautiful in their rough and crumbling state, to me they are perfect reminders of the non-royal Egyptian people who left their marks on history in amongst the coffin wood.

The foot of the anthropoid coffin.

We look forward to seeing you next Tuesday for a new digging diary!