Discover the Collection

Our Collection

The Museo Egizio, with its extraordinary collection of statues, papyri, sarcophagi, objects from the daily life and, of course, mummies, is deemed to house the biggest cultural and scientific collection in the field of Egyptian antiquities outside of Egypt, in other words it is second to the Museum of Cairo.

Collection Highlights

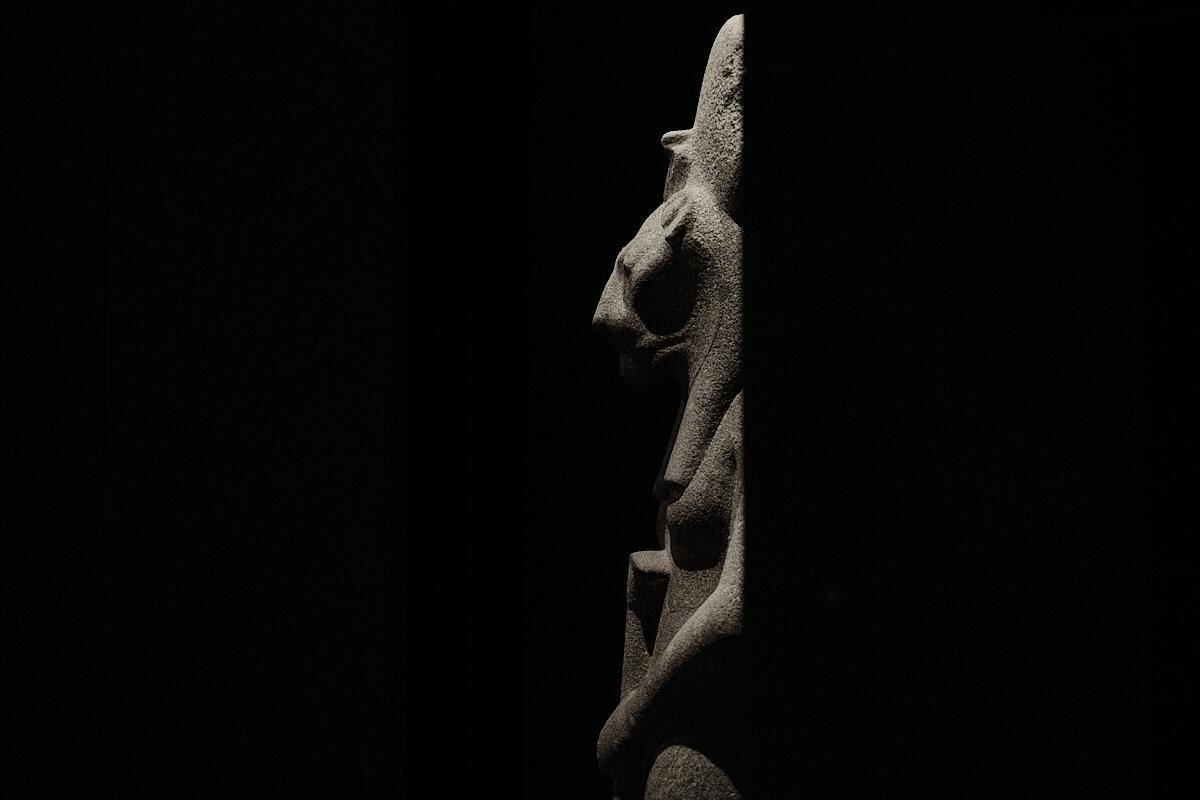

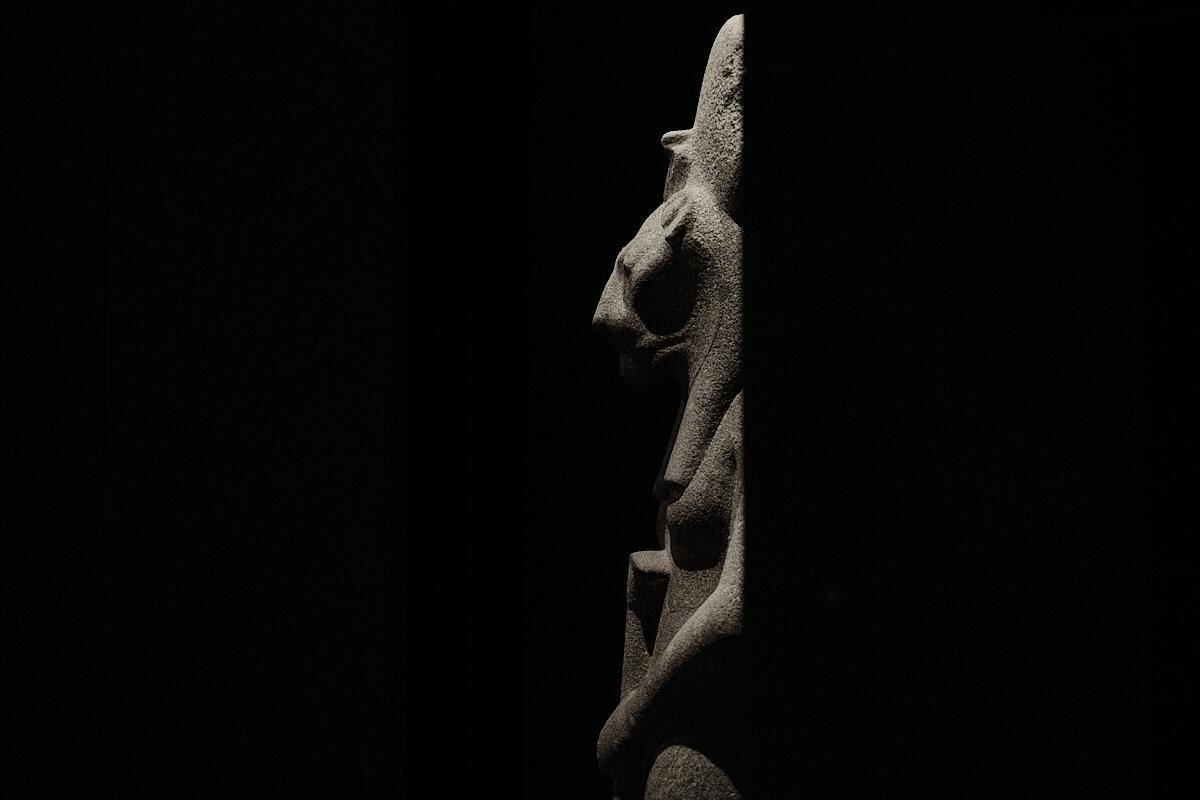

The statues of the goddess Sekhmet The Museo Egizio has many colossal statues of the goddess Sekhmet. These sculptures all belong to a very numerous series, specimens of which are found in many Egyptian collections in the world and at several sites in Egypt. Most were discovered in the temple of Mut in Karnak. It is possible that even during Amenhotep III’s reign, these statues of Sekhmet were installed in several temples, According to another hypothesis, they originally all stood in the ‘Temple of Millions of Years’ of Amonhotep III (1390-1353 BC), on the site of Kom el-Hettan (western Thebes). These statues were used for daily rites which allowed the king to regenerate and ensure the equilibrium of the cosmos for eternity.

Predynastic burial Predynastic Period, Naqada II (ca 3600 – 3350 BC). S. 293-303. This mummy was purchased in Egypt by Ernesto Schiaparelli in the early twentieth century. The body is that of a man who lived in the Predynastic Period, before Egypt was unified. The deceased was buried in the usual foetal position in the desert sand. The technique of mummification was not yet developed in this early period, but the dry warmth of the desert allowed the body to desiccate and mummify naturally. Traces of fabric and matting in which the corpse was wrapped are still visible on this skin of this ‘natural mummy’. Hunting weapons (arrows and throwing sticks), baskets, leather bags and sandals considered necessary to the deceased were usually included in this type of burial.

The coffins of Butehamon Third Intermediate Period, early 21st Dynasty (1076 - 1056 BC), Deir el-Medina. C. 2236/1, 2237/3. In the Third Intermediate Period in the 10th century BC the wall paintings and funerary texts were transferred from the tomb walls to the coffins that became quite elaborate. Butehamon, the royal scribe of the necropolis, was buried in this double anthropoid coffin, distinctive for 21st Dynasty with an extra protective inner ‘false’ lid. The deceased is depicted on the exterior lid holding the djed-amulet (symbolizing the spine of Osiris and endurance) and the tyet-amulet (a protective knot). On the internal lid he holds the feathers of Maat, the goddess of justice. The rest of the figure is decorated with sacred texts, which border religious scenes.

Ostracon showing an acrobatic dancer New Kingdom, 18th – 20th Dynasty (1292 – 1076 BC), Deir el-Medina. C. 7052. Papyrus was an expensive medium reserved for official documents, so that potsherds and flakes of limestone (ostraca) were normally used instead. The uses were disparate such as for contracts, receipts, letters, stories, writing exercises and even doodles provide an insight into daily life. This magnificently drawn sketch of a lady doing a back bend defies many of the conventions of Egyptian art. The lady is semi naked, wearing a black sarong and gold hoop earrings and is depicted in perfect profile, doing an elegant back bend. Her wavy hair flows wildly free, but her earring defies gravity. The liveliness and quality of draughtsmanship of this semi-erotic sketch, demonstrate a high level of skill and certainly suggests that it was the drawing of a royal artisan working in the Valley of the Kings.

Gebelein painted linen The Gebelein cloth is the oldest known example of painting on linen so far, dating back to 5,000 years ago. It was discovered during the excavation season carried out in 1930 by Giulio Farina, in the Predynastic cemetery of Gebelein. The object is painted with red, black and white pigments, and shows scenes of life on the Nile, with boats and human figures engaged in various activities. The themes depicted concern a moment of ritual aggregation probably related to the celebration of one or more events related to religious worship or social ceremonies. Various activities are represented: a procession of boats, with rowers and passengers painted in red and depicted in profile; a "dance" of figures dressed in a long black skirt with their arms raised to the sky, facing downwards, or holding hands; and a hippo hunt. Given the complexity of the subjects, not all scholars agree on the interpretation of the functions and intended use of this artefact. The object was found fragmented into numerous pieces which were recomposed into four panels during the thirties of the last century

Animal mummies – Mummy of a bull Egyptians gods manifested themselves in various forms and many were associated with specific animals. The practice of mummifying animals is documented in Egypt since the Predynastic Period (before 3000 BC), reaching the peak of its popularity in the Late Period, to finally disappear at the end of the 4th century BC. A specially selected specimen of the animal associated with a given deity was worshiped in this deity’s temple and regarded as its incarnation. Upon the animal’s death, the body was mummified and placed in a sarcophagus or coffin. Other animals were mummified and brought to the temple as votive gifts. The bull was associated with the god Api, royal power and the concept of strength.

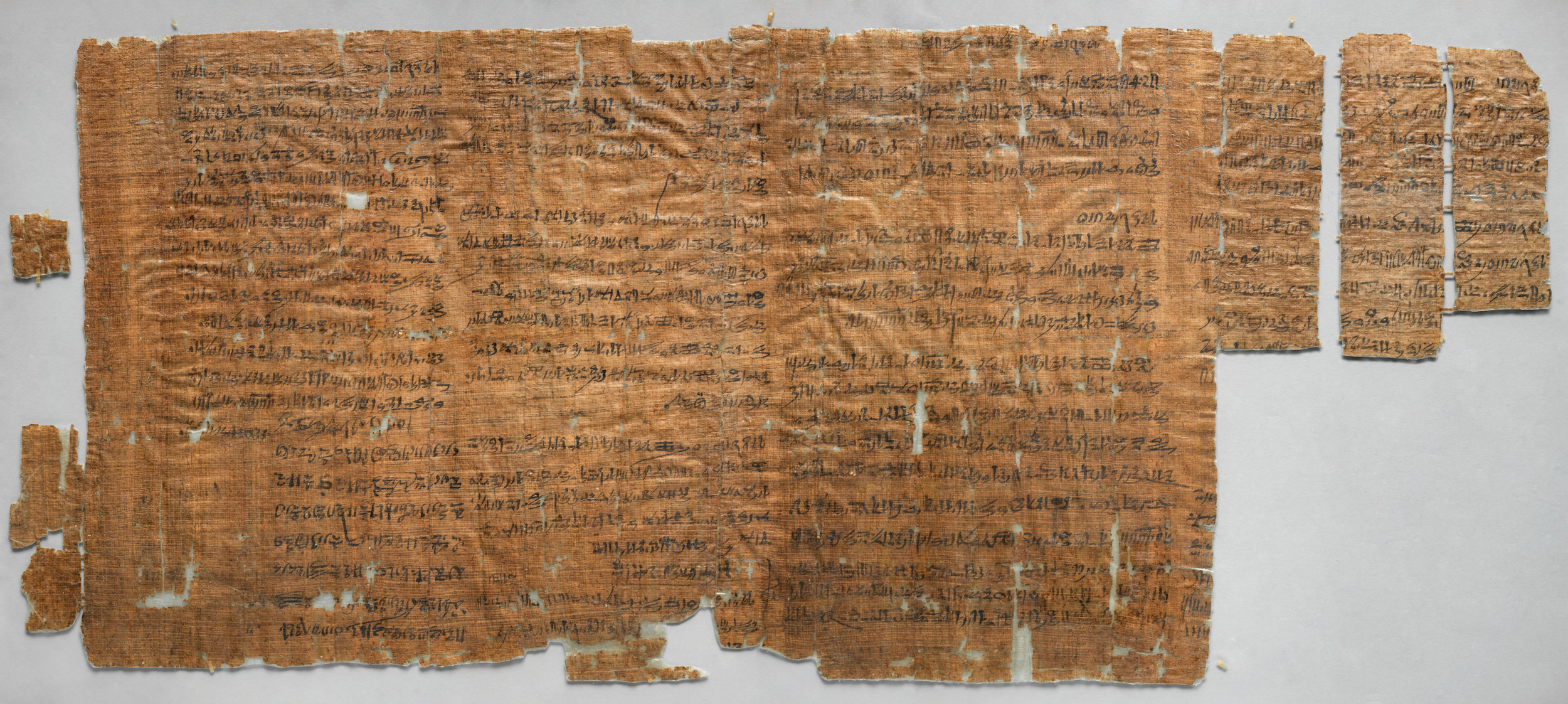

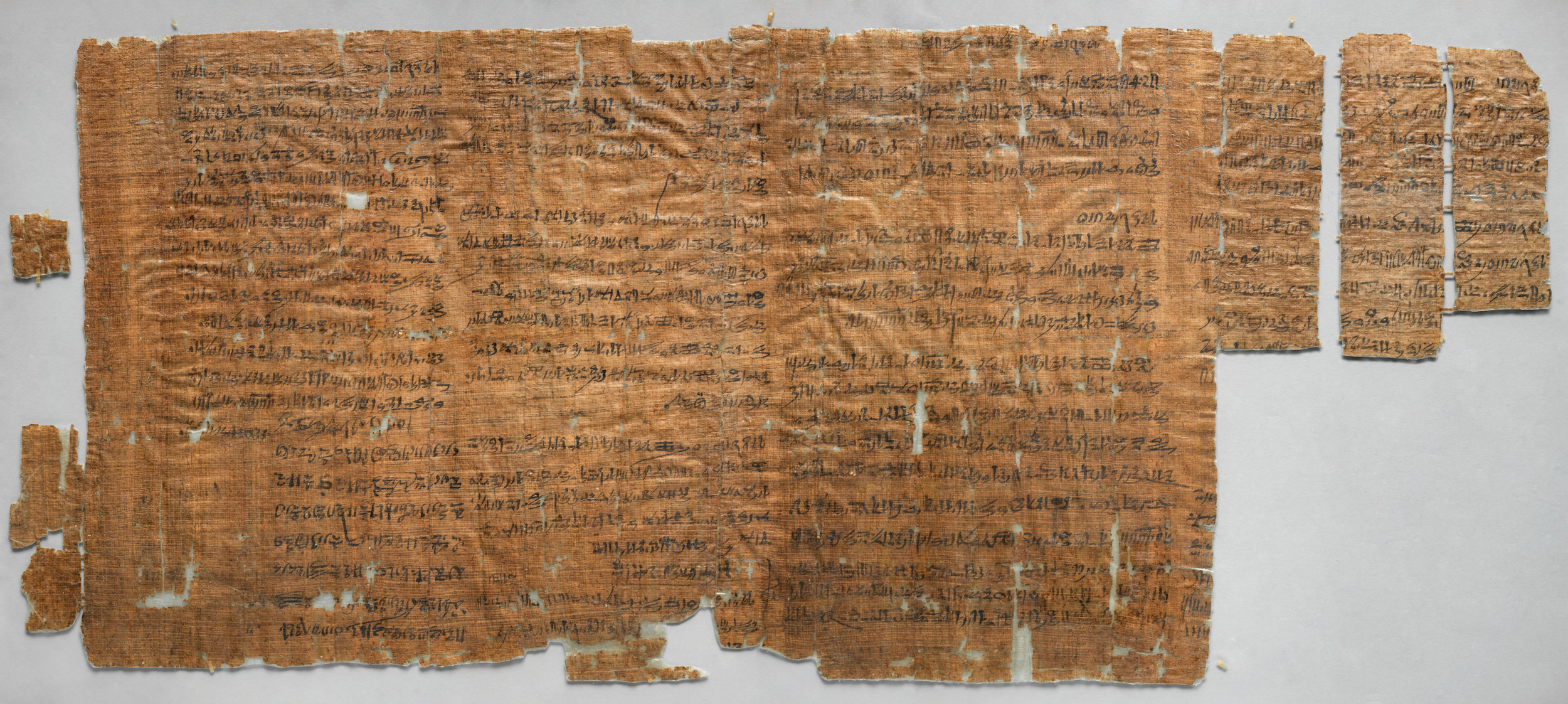

The Strike Papyrus New Kingdom, 20th Dynasty, reign of Ramesse III (1187 – 1157 BC), Deir el-Medina. C. 1880. The so-called “Strike Papyrus” is a hieratic (a cursive form of ancient Egyptian writing) administrative papyrus reporting the news of a strike that took place during the reign of Ramses III. The report on the papyrus was written by Amunnakht, scribe of the “Goldmine Papyrus” and the “Tomb Plan”. The workers protested because they had not received their regular food rations, which constituted payment for their work in the Valley for the Kings. Despite various attempts at conciliation, the protest lasted a number of days. To the officials who tried to persuade them to return to work, the workers replied: “We are here because of the hunger and thirst… Write to the pharaoh our perfect lord, take note of our words, and write to the vizier our superior because we are in need of our provisions”.

The statue of Ramesses II New Kingdom, 19th Dynasty, reign of Ramesses II (279 – 1213 BC), Thebes, Karnak / temple of Amun. C. 1380. This granodiorite sculpture from Thebes is world renown as the highlight portrait of one of the most famous and longest reigning pharaohs: Ramesses II. The king wears the Blue Crown, or war helmet, probably made of leather and inlaid with metal rings, and a long-pleated robe that is asymmetrically draped to create an enormous bell sleeve. In his right hand he grasps the heqa-sceptre of rulership and his feet are shod in sandals. The statue is a beautiful example of the art of the period: the dress, the sandals and the pierced earlobes resume the typical fashion of the previous Amarna period. This statue is one of the symbols of the Museo Egizio. In a letter that he wrote during his stay in Turin in 1824, Champollion describes with enthusiasm “the beauty and the admirable perfection of this colossal figure (…): for six whole months I have seen it every day, and always I have the impression of seeing it for the first time. The head is divine, the feet and hands are admirable, the body is voluptuous; I call it the Egyptian Apollo of the Belvedere … in short, I am in love with it.”

Funerary Mask of Merit New Kingdom, 18th Dynasty, reigns of Amenhotep II, Tuthmosis IV and Amenhotep III (1425-1353 BC), Deir el-Medina, S. 8473. The mask was found in 1906, in the precious burial assemblage of the Tomb of Kha and his wife Merit. The mask is made of cartonnage, a sort of papier-mâché made of stripes of linen soaked in gypsum, glided and decorated with semi-precious stones and glass. According to Spell 151 of the Books of the Dead, the purpose of the mask is to protect the deceased and restore his sight. The use of god and lapis lazuli describe the divine status of Merit, now an incorruptible spirit.

Mensa Isiaca Mensa Isiaca, 1st century AC, Rome, probably from the Iseum Campense, formerly in the Gonzaga collection. C. 7155. Pursuing an ambitious project to endow Turin with a “Great Gallery” of antiquities, between 1626 and 1630 Charles Emanuel I of Savoy ordered the purchase of a lot of objects from the collection of the Gonzaga dukes in Mantua. Among them was the so-called “Mensa Isiaca”, a bronze table representing the goddess Isis surrounded by other Egyptianized divinities and hieroglyphic signs. Made in the first century AD, probably in Rome, it was presumably meant to grace the altar od a temple of the goddess Isis, possibly the Iseum Campense itself. Its discovery, in 1527, intrigued many scholars interested in the interpretation of hieroglyphs that were later understood to be only decorative and meaningless.

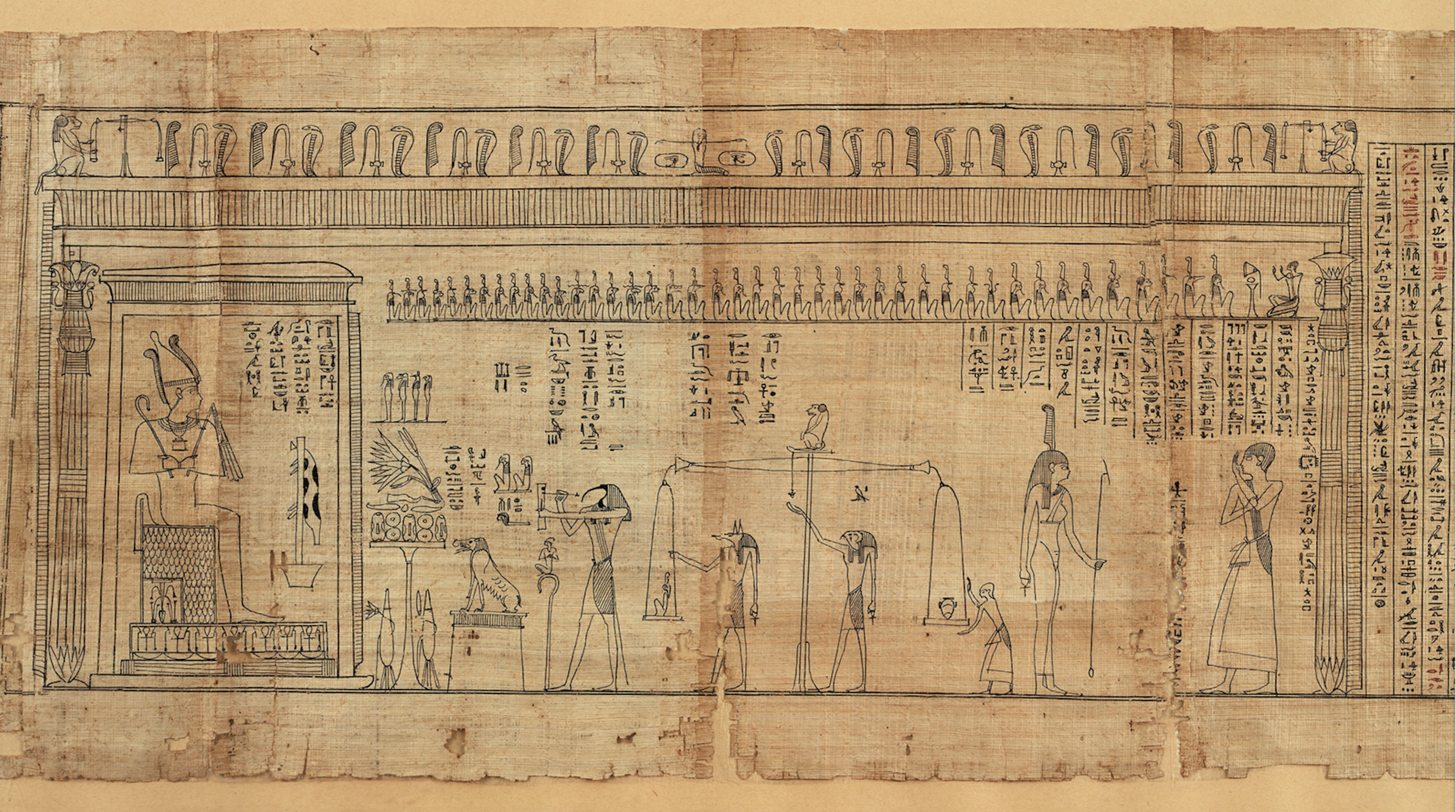

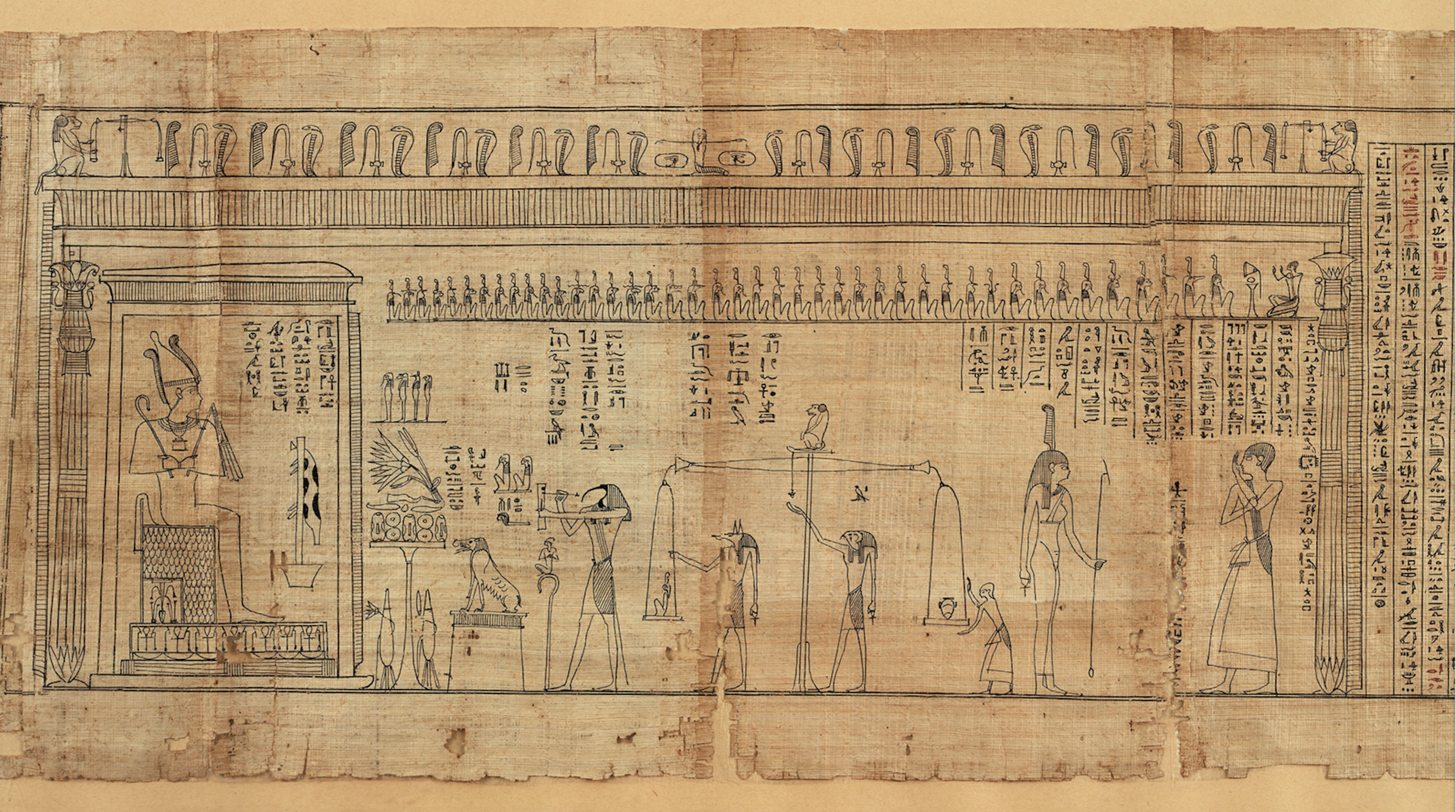

The Book of the Dead of Iuefankh Ptolemaic Period (332 – 30 BC). C. 1791. The papyrus, which is 1847cm long, is part of the funerary equipment of Iuefankh, it comes to Turin with the Drovetti collection. The name "Book of the Dead" was coined by Richard Lepsius, a German scholar, to indicate the set of funerary formulas that, starting from the New Kingdom, were written on papyrus and included in the funerary spells to guide the deceased in the hereafter. Thanks to the good preservation of the papyrus, Lepsius was able to study it, starting to classify the text into chapters and establish a canon of reference that is still in use today.